The old district of Bab Al Hadid, the Iron gate, surrounds the ancient Citadel and its hill. In the neighborhood, every battalion has its own front line, except for larger brigades who fight on more then one.

A woman with more then one stray wisps of hair poking out from under her veil, and ash blond at that, walking down the cobbled streets of Bab Al Adid, waving to a stranger, didn’t fail to impress commander Sheik Kattan, who pulled over his pick up to engage in conversation. He is in charge of the artillery of the Ahrar Syria brigade ( the Free people of Syria) one of the largest in the city, about 5000 men, and he is willing to show us the rebels’ experiments at casting their own barrels. On the way, he lifted the cover of an intriguing tunnel, looking from the asphalt like the regular cover of a city conduit, but used instead by the rebels to penetrate into enemy’s neighborhoods.

Where exactly the tunnel would end up, he wouldn’t say.

At the command center, he produced for us the performance of fire by lighting what he called magic cotton, which is regular medical cotton which underwent a chemical treatment with potassium nitrate, ammonium nitrate and acid. “What kind of acid?” , I asked him. “Acid, just acid.” As a result, the cotton becomes highly inflammable and it’s used, as he demonstrated, to fill up plastic cartridges to be inserted in equally hand crafted guns.

“Where did you import the process from? Afghanistan?” “No, we were discouraged because nobody wanted to help us, so we searched the internet”. Commander Kattan then proceeded to show us a home made rpg shell which costed him 5 dollars to make, as opposed to the ones found on the dried up Lebanese market for 800,000 dollars.

The 140 mm artillery and the shell which he dropped in it were also products of their own experiments in metallurgy , and so were the 3 kg missile and its launcher.

The jewel of the ammo was an ingeniously thought out dynamite launcher gun they nicknamed bombaction: the empty casing of a doshka bullet is filled with dynamite powder, then dropped into the tip of the gun. A cartridge filled with magic cotton is then placed inside the gun, which gets ignited at the triggering, thus propelling the dynamite launch.

Asked if the defeat of Qussair represented the loss of a supply route and troops to the Idlib province, Mr Kattan replied that the road was still in use, and they withdrew temporarily just to save civilians lives. “In Aleppo, we pushed the shabiha back to their neighborhoods and the citadel is ninety per cent taken”. Then we asked Mr Kattan to take us to the real thing. His men took us to unsuspected front lines, on the top floors of ancient burned buildings concealed by regular looking facades, up on the familiar tour of the rubble:

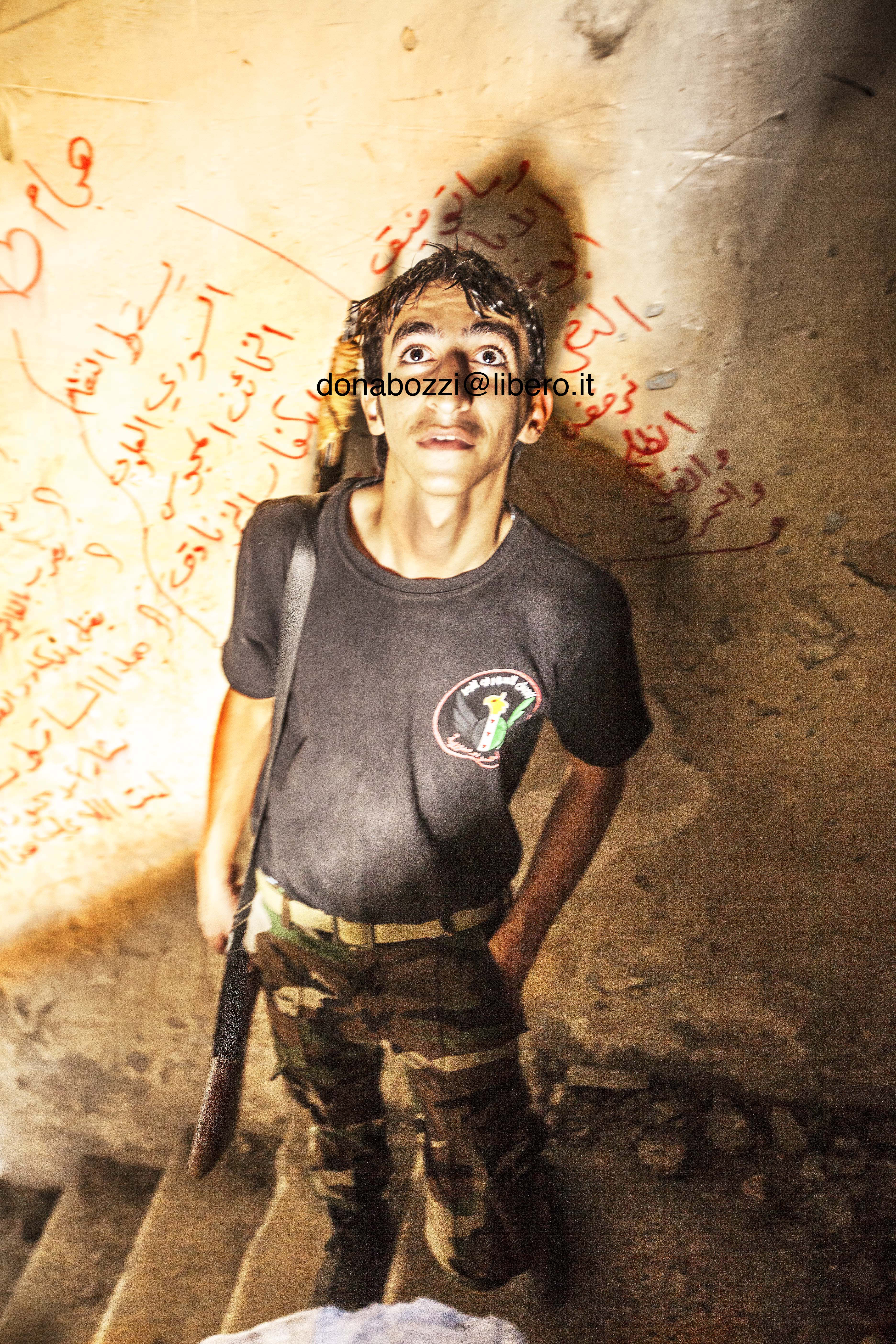

In Aleppo’s Bab Al-Hadid neighborhood, or Iron Gate, between buildings held by the Free Syrian Army and the regime, shouts, then fire, were exchanged. The men of the Ahrar Syria Brigade (Free Syria) were the stokers; with temerity, they yelled “Shabiha! Shabiha!”, through rubbly breaches, standing around a building corner, atop ramshackle roofs, into surrounding regime held blocks. Annoyed that the mice hadn’t come out of their holes yet, they continued to shout insults: preferring to wait for darker hours, the Shabiha didn’t accept the invitation. So we would wait too, standing with our back against a putrid wall, feeling unsheltered as we looked out the wall-less side of the kitchen, now become an unglazed panorama over the remains of the Iron Gate.

Our friends, pointing at the snipers’ shots on the wall behind our shoulders, advised us to move over to a surprisingly safer spot: right in the open. We preferred to move. While moving building to building or even from a kitchen to a bedroom, missing or broken wall occasionally exposed us to the Shabiha’s view. We were thus advised to run. And so we did along the sniper alleys of the Iron Gate, back to the future from the siege of a city in a previous European war, two borders up, promised to be the last mass grave, the last stolen country.

Back to Bustan Al Qasr. Toni, the head of the AMC, proceeded to recount the real story, or history, of ISIS: “More and more Iraqi fighters were coming in, joining Al Nusra, sent in by Abu Baker Al Baghdadi to cause trouble, starting to interfere with people’s lives and kidnapping journalists. Baghdadi himself announced the merging of the State of Iraq with Syrian Al Nusra (the Sham); that made the Iraqi elements feel entitled to steal our weapons and money. Al Nusra’s high profile men lost control, and kept their head low, waiting for orders from their chief Al Golani, who declared he did not want to merge with Abu Baker and ISIS, however he did pledge allegiance to Al Zawahiri as a leader and a person, but not to Al Qaeda as the group. Al Zawahiri then disbanded the merger (we forgot to ask if he did encouraged it in the first place) and ordered Bahgdadi back to Iraq, and Golani to stay put, thus encouraging fighters to defect back from ISIS to Al Nusra. Baghdadi violated Zawahiri’s order and stayed in Syria, thus radicating terrorism in our Country.

Back to our rooms, we celebrated a long awaited trickle of water, tapping into the resource at a prodigious rate to fill a dozen bottles before it came to an end, and taking showers as if there was no tomorrow. Then by the light of the beam of the open mac book we went downstairs, mischievous kids popping out of dark corners, one of them pulling a serious kitchen knife out of the dark, all he had found to play with.

In the heyday of the Aleppo revolution, supper was extravagant even for spoiled western European standards: about twenty kids would take a break from laptopping the revolution, stand around a chairless table, stick their bumpy flat bread into tahini butter, made from freshly ground sesame, picking up roasted chicken with the folded circles, complaining that the cook wasn’t up to snuff, and wondering if I had a younger sister.

The first jihado nicknames however would start to bubble up on FB, and bad looking dudes in black with guns at the AMC gate, would gesture unfriendly to us “picture verboten”: the media center was soon to become an oxymoron for journalists, along with the fact that the regime, probably according to a “pattern of life behavior” had started to pick on us with what sounded like grad-thuds on our roof around 5 o’clock am.

But times were changing, as experienced by this writer, caught one morning inadvertently veilless at breakfast: veilless at breakfast is anathema enough in any Muslim country, even in tolerant not yet beard peaked Aleppo: Sami, our fixer, revealed that rumors had been circulating in the building about an undetermined number of wisps permanently poking out from under my hijab. The Administrator, look from jihadi central casting, disclosed a long buttoned up feeling, unbuttoned: he drew endless loops with his index finger around his face, meaning “the veil”, then he flashed his swinging open palms up at me, clearly conveying the international “that’s it” injunction. We were escorted to the available ramshackle car, Sami in the front seat, as an interpreter if needed. We drove up north 20 miles from Azaz, where we were courteously dumped at a bus stop, not in an unfriendly manner, bus fare to Kilis courtesy of the house. Sami ordered to write as soon as we had crossed the border, and I obliged to his 10 years older then real birthday Fb profile; he confirmed to my next fixer, that he “protected me as a woman in a warzone” and reiterated not to worry, it’s not uncommon that Syrian may be wary of journalists, even those who not so covertly root for the revolution.

russian backed pro regime forces arrive in #Raqqa Russia who’s allied w/US who’s not so allied with regime, or not?https://t.co/9ikowWSsv4

— dona bozzi (@donabozziblog) May 21, 2017