The Syria Portfolio

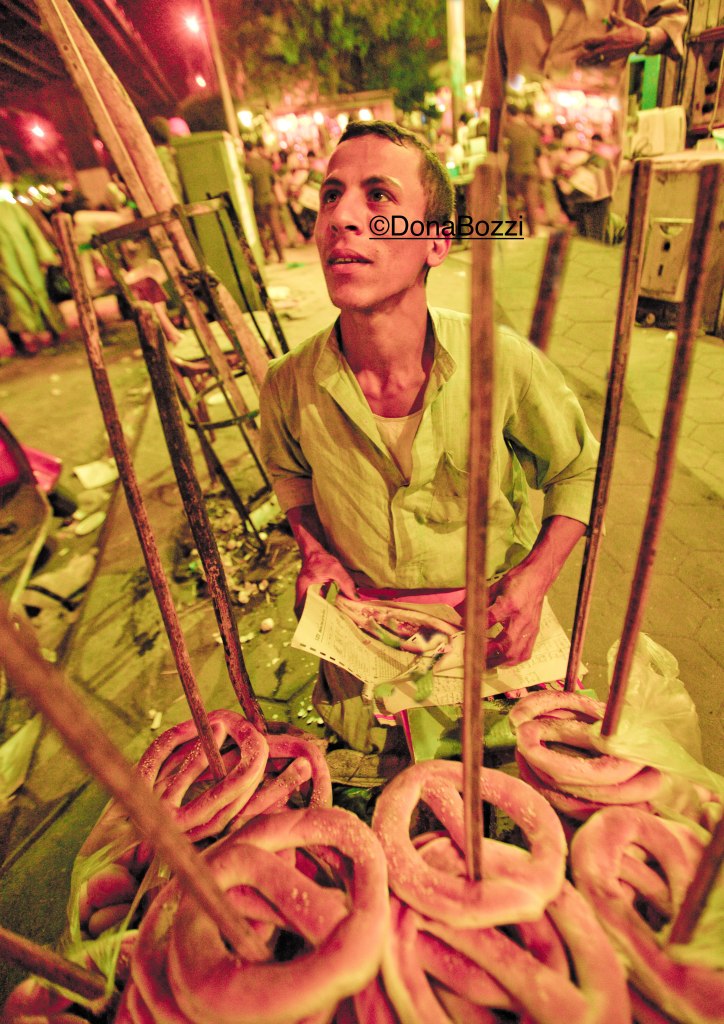

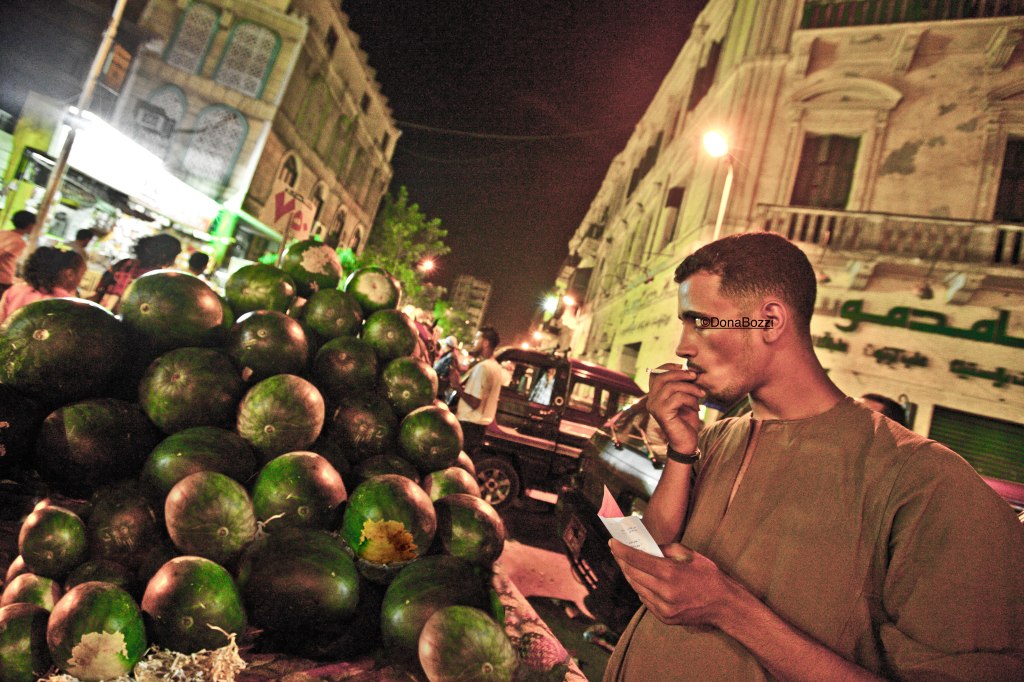

Hebron, West Bank,July 7 2009. The main market

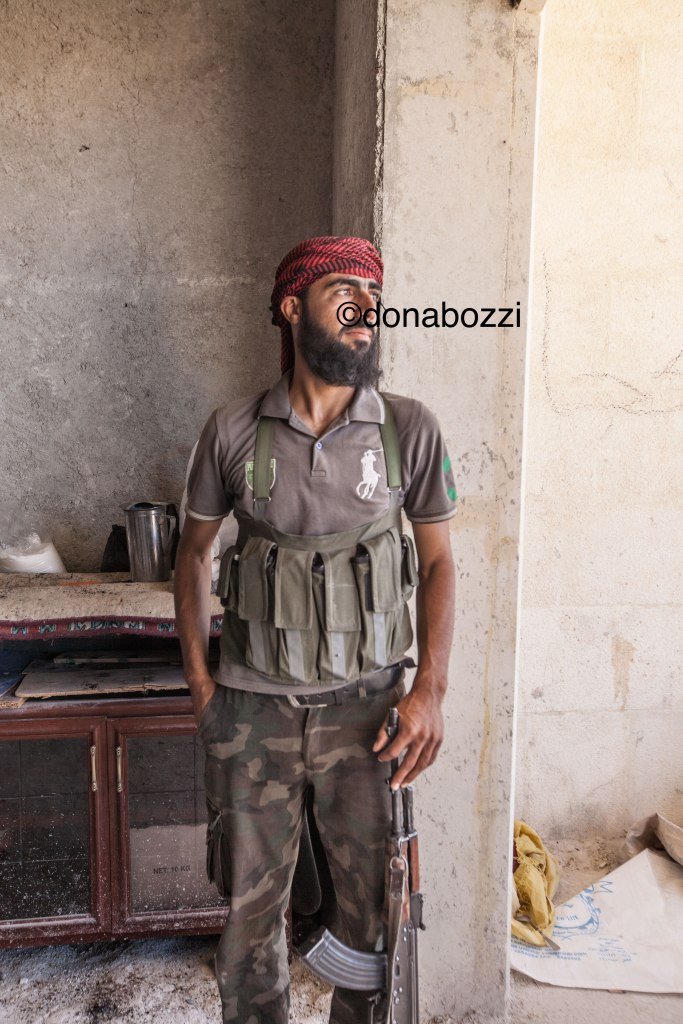

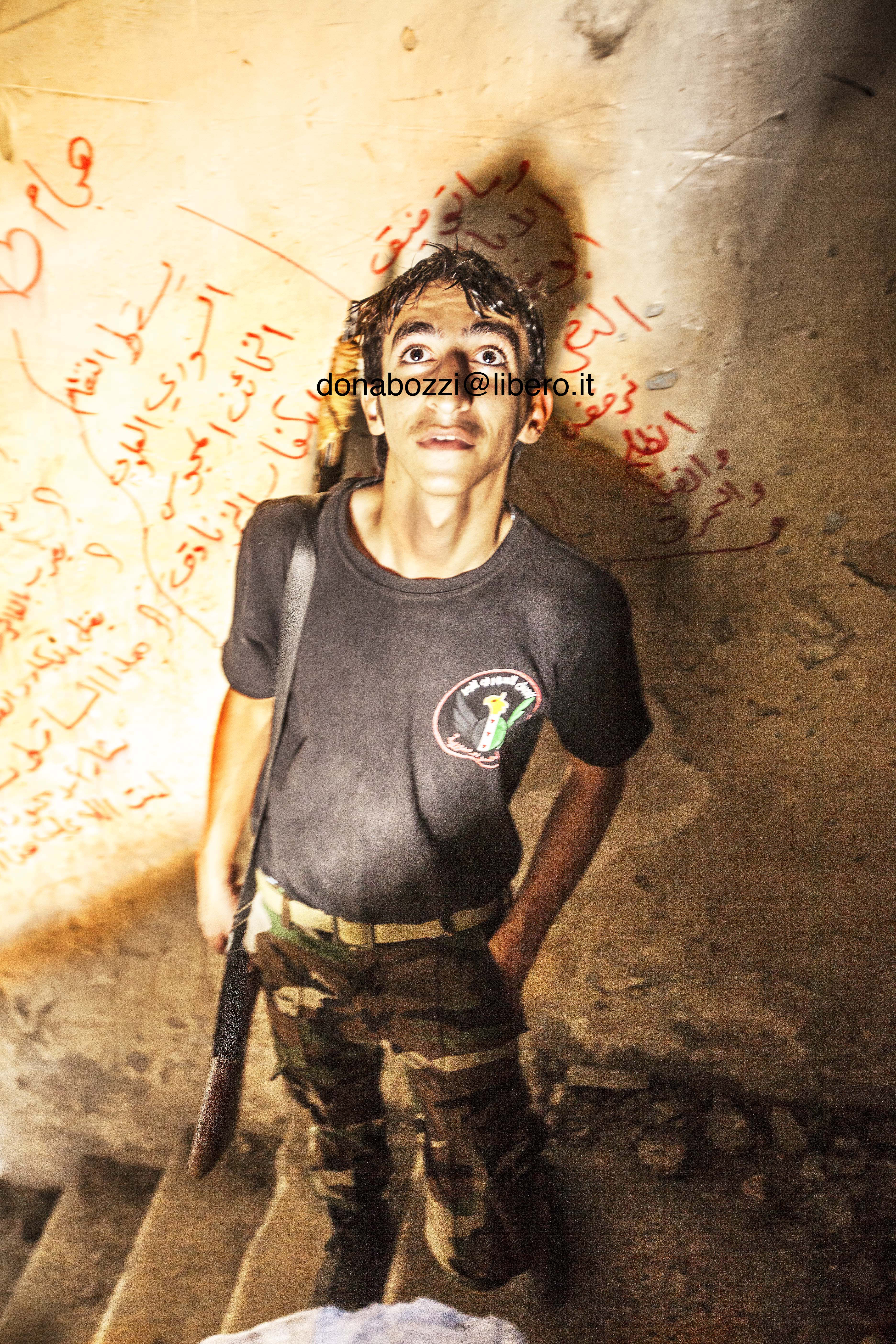

Summer 2013. In the Aleppo countryside, the Al-Aqsa Brigade of the Free Syrian Army fires down below at the Hezbollah militias who have penetrated the villages of Nubbul and Zahara.

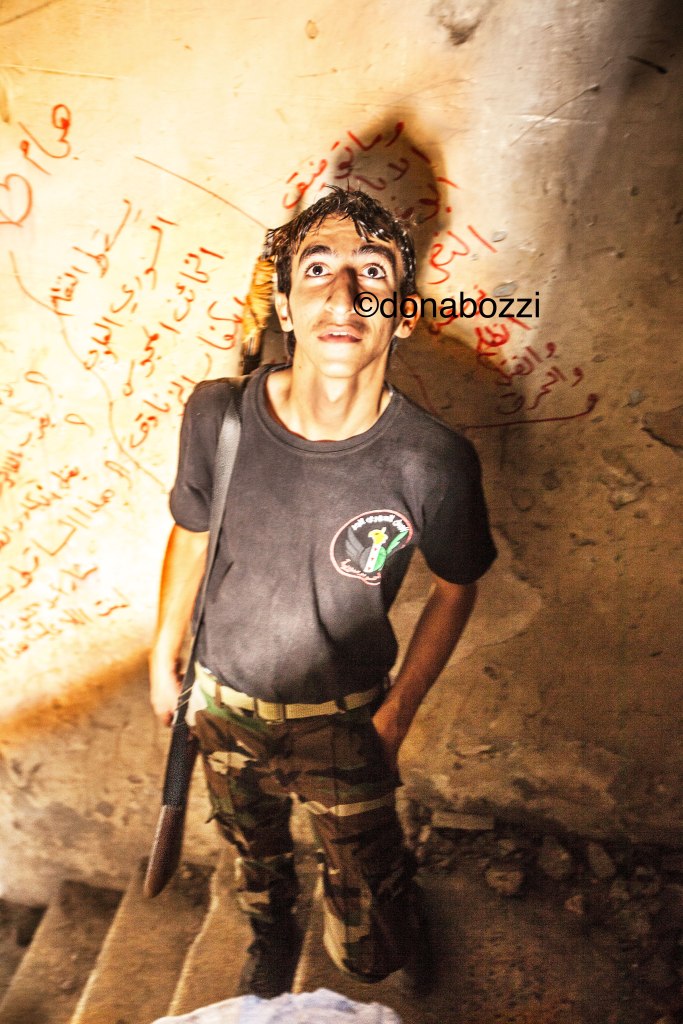

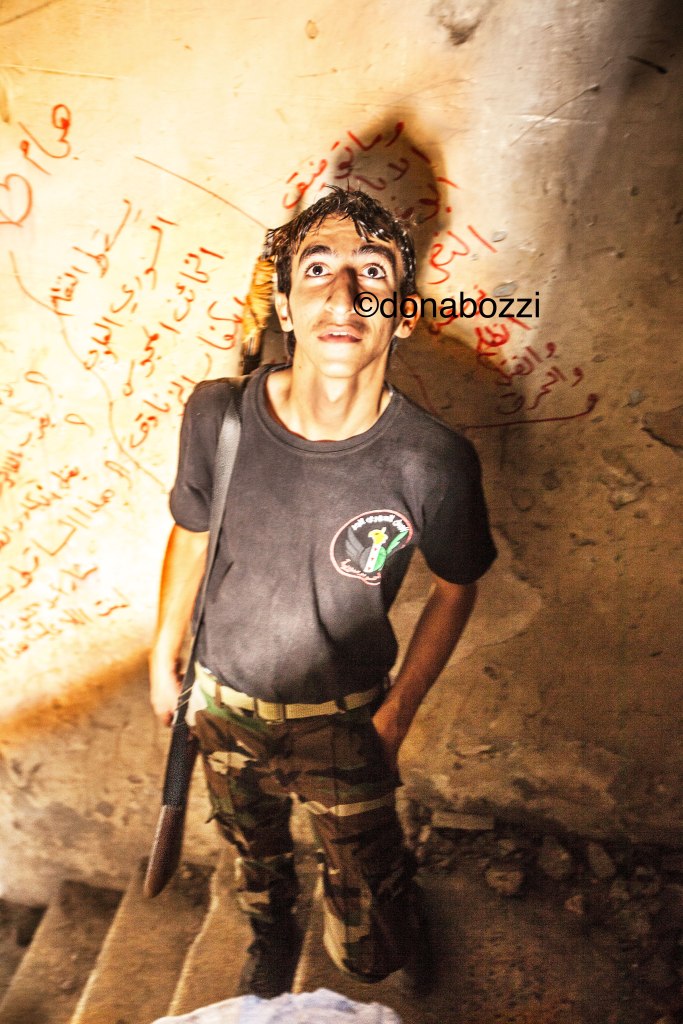

Of all the FSA commanders we met, Yaser Sokar, head of the Al-Aqsa brigade, an unprejudiced, soft-spoken man, is the only one who dared to shake our hands, wiping his own afterwards as a joke. The villages of Nubbul and Al-Zahra have been penetrated by Hezbollah; “Can the siege be broken by the SAA?”, we asked him. “No, never, we’ll eventually rout them out!” He gave us the green light to go to Jabbal Shewehna, a front line at the bottom of a hill a few kilometers from Hraytan. The Al Aqsa fighters stand on one side of the hill, and the regime troops stand on the other. “If we take this hill top, we’ll take all of Aleppo!” says one Al-Aqsa fighter, still foolishly trapped in the magical thinking of victory over “Gaahesh”, that’s what they call Bashar here from the donkey’s genes that shape his face. The rebels complained about the enemy’s superiority given its use of the Shilka, a tank with a sniper capable of shooting 2400 bullets per minute.

The FSA fighters have received a few Concourse missiles, basically zapper guns, but still lament the weapons of the poor. They particularly badly need RPG-type of rocket that can better track and follow enemy targets, primarily the Russian made T-72 tanks.

The FSA base, a huge barrack behind of a two-kilometer long wall used for sniping through the breaches in it, “is manned by about 400 men, or so the regime thinks!”, says a young fighter, laughing.

Standing out beside an antique mystery cannon and home made attempts at casting their own barrels, is a “Dushka” machine gun, pilfered from the regime and fitted with a 14.5 mm cartridge that can release 300 bullets per minute.

Commander Yaser Socar’s dinner invitation had an hidden agenda; it was a cry for help. The comfortably furnished rooms of his house exuded culture and open mindedness, and moderate wealth. Too unpretentious to present us with an exclusively Syrian meal, he added a European-type of course to the dinner to make us feel more comfortable. Then he exclaimed, painfully:

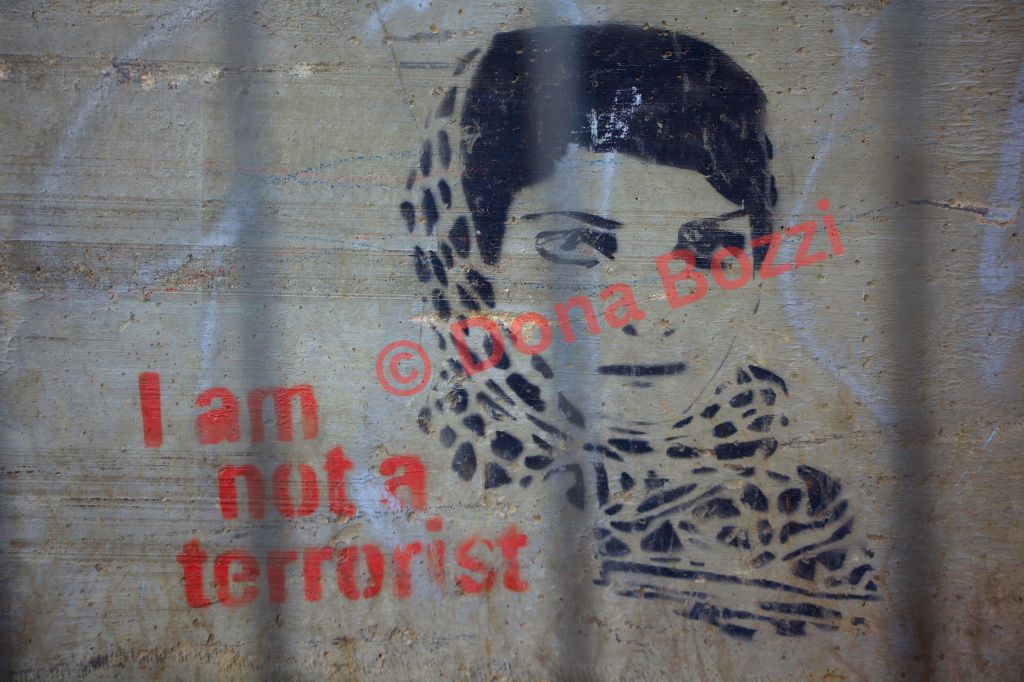

“We are the real Muslims of Syria. Do we look like terrorists to you? They killed our children, they burned our houses. Did they call them terrorists? We are the ones they called terrorists! The true terrorists were released by the regime in 2011 from Saidnaya prison, under pressure from the international community in the first few months of the uprising, as part of a smokescreen amnesty.

Our battalion, the Al Aqsa Brigade, didn’t get all the media attention that Al-Tawheed did, and therefore didn’t get the needed military supplies from Qatar that they did. We didn’t even get enough bullets from the military council of the FSA, let alone foreign powers!”

He said he would take us on the following day to Nubbul and Al-Zahra, two Shia villages on the outskirts of Aleppo, with a combined population of about 5000, where Hezbollah reigns and even the women carry guns. Here, the Al-Aqsa men enjoy a formidable vantage point: the terrace of yet another elegant private mansion turned into an FSA headquarters. We were actually facing Nubbul and Al-Zahra from about three kilometres away. The rebel’s elevated position above the villages definitely gave them the upper hand. Suddenly, the men ducked in a row behind the terrace wall to exchange fire. Suddenly, one of the Al-Aqsa fighters shouted “Allahu Akbar,” leaping excited with his Kalashnikov lifted in the air. It then became still. He had just killed a man. When asked why Hezbollah woudn’t dare to retaliate the injury, they said that daylight doesn’t allow them to clash comfortably enough. All throughout the clash, our fixer and our friends held their back glued to the terrace floor. On it, lay a dozen or so empty bullet casings landed from the other side.

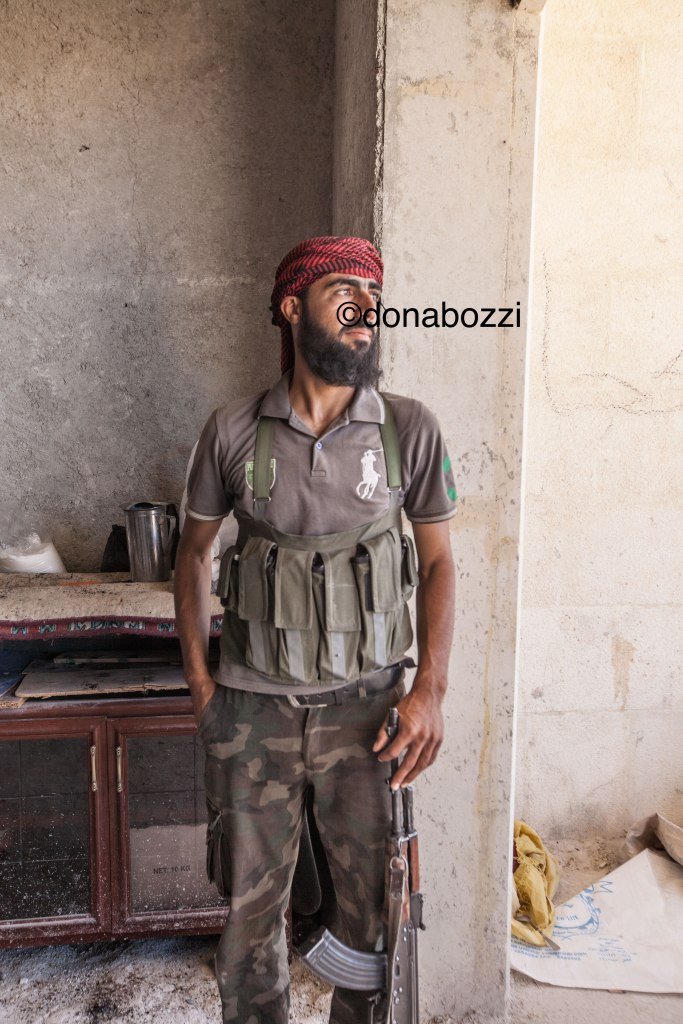

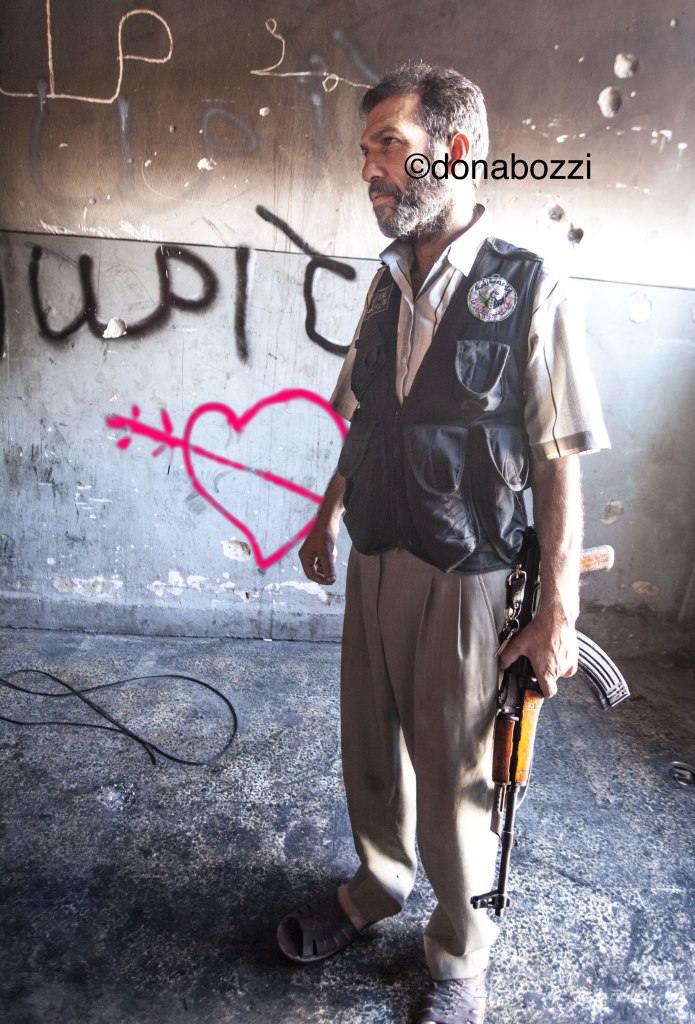

Zakaria Jrab, leader of the Katiba Shams Alhak (The Sun of Righteousness), is a member of the military commitee of the Council of the Governorate of Aleppo. I asked him:

“Mr. Jrab, what is the ideological difference between Ahrar Al-Sham and the FSA? The way Ahrar members dress, in black from head to toe and wearing black kohl around their eyes, is not exactly reassuring”.

“There is no difference between the two: we are brothers, we coordinate with each other on the front line. However, Ahrar Al-Sham is more devout and more rigorous in the observance of the Sharia then the FSA, where some elements may be nonchalant or plain aloof. We can definitely say they are Islamists, but we work together because they are not radical.”

“Does the FSA has more affinity with Ahrar Al-Sham than with Al- Golani?” Ahrar Al-Sham is easier to deal with, more open minded and doesn’t have an agenda. Mr. Golani wants to take over the country after the revolution.” “Why can’t you get good antiaircraft from the United States, like Turkey did? “Because the United States has a precondition: they want to give Idlib and Aleppo to their ally, Turkey.”

” What about Qatar? Why they don’t help you more?” “Because they don’t have the OK from the United States. Recently a shipment of RPG made in Austria, from the UAE to Syria, was stopped by the United States. The regime has Shilkas with snipers capable of shooting 2400 bullets per minute. We have 45 mm “Dushka” machine guns at 300 bullets per minute”

And a sleek, albeit quite lonely, M16 from the United States; plus, of course, MRE, “meals ready to eat”, repurposed from Iraq and Afghanistan. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33997408

“I request that I be investigated for my role in the old regime, even as president, by a new judicial…” http://t.co/gkjSDUAg

— LIBYAN REVOLUTION (@LIBYANREVOLT) November 23, 2011

Tobruck from Cairo: the humble donkey cart stopped at Saloum, intimidated by the wealth beyond the custom barrier. In the waste land to the border, we took several lifts from private cars and quite a few among them, even if welcoming, did not shy away from recommending tips.

That wouldn’t happen in Libya: if you are a foreigner, don’t try to pay for buns at the bread line in Misrata, and don’t try to wait for your turn either. When the oven doors open, you are invited to take a cloth and help yourself to the hot buns, then at the cash, a flashed open palm, slightly pushed forward, indicates that even if you are a regular with two baguettes you are free to go.

Benghazi Freedom Square had been rehearsing for months, the celebration of the impending mad dog’s fall, 4 months before a bullet blew his head: 40 km west of Misrata, the rebels were pushing the front line further west every day, “container by container”, boasted Tribute fm 92.4, the English-speaking radio operated by Libyan expats returned from London in order not to miss the inevitable.

On the promenade along the sea, amongst the loads of wearable memorabilia with the Libyan star and moon, the colors of the European creditors of the revolution were for sale as bracelets, or waving tall on flags, together with those of the overseas allies of the free world. Whoever engaged in conversation prized their favorite western sponsor: “Sarkozy, Italia, myamya!” (Libyan for excellent, they never heard it in Syria). Some kids were passing USB keys to the journalists, containing images of babies burned by white phosphorous in Misrata. The facade of the Courthouse was completely covered by a mosaic of faces. The man requested who they were lowered his head and shut his eyes: “They are the “shahids”, the martyrs of the regime from 1969 until the battle of the Katiba, the government garrison conquered by the rebels in February 2011.”

The women in black from Freedom Square, then aging, where holding framed portraits, bearing the likenesses of their own children, between their twenties and thirties, victims of the Abu Salim massacre, back in 1996, when 1200 regime opponents were machined-gunned in barely 137 minutes.

Back to the hotel, the manager himself was watching burned bodies from the Misrata shelling, and so did we, some were babies wrapped in white shrouds. Then he recommended to get black veils to go around, which we did at the souk, for 5 dinars, from a merchant who took 20 and forgot to give us back the change. At the ensuing riot, the Libyan men at the souk deliberated that the merchant was “No Libyan people”, claiming that national moral code which came up up again subsequently for, perhaps amongst other reasons, the sake of the Libyan reputation abroad. Misrata committee, Benghazi port. We were ordered to enter the ladies’ waiting room for the ship to Misrata, which was also a prayer area. The ferry fare was 70 dinar for Libyans and 150 for foreigners (one way), a surprising double standard because “everybody must pay according to their means”. The night passage of about 450 km west was secure, the staff guaranteed, because “NATO approved”; the boat, full. The passengers were so closely packed together, that a man’s toe, who was lucky enough to have found a chair, was dangling on the open mouth of a snoring man, lying on the deck. Most of them were Misrata residents, bringing back rare goods, like cheese, coffee, cigarettes. The free alternative, a fishermen’s boat, which was also carrying a few shababs, the men at war, was expected to have a duration of 50 hours.

The magic word to reach the front line sounded like a code name: Dafniya, literally Land of Farmers, End of Misrata, seemed to stand for the front line as well. Just mentioning to the rebels when they stopped their pickups, would provide us a lift 40 miles west to a shipping container, overflowing with sand, as a makeshift rampart to block the road. Further up, more containers were marking subsequent gains of ground. With civilian cars it didn’t work, we were sent back to the checkpoint. The advance “container by container” from Tribute radio was finally realized: a fresh container, marking the farthest position of the front line, was added each time a jump ahead was produced, thus leaving the preceding ones behind, a line up of staggered blocks where the pickups would zig-zag right through, a quite familiar maze for them. Overflowing with sand to deter the impact of bullets, the containers were an ingenious concept born out of necessity, like the UB-16 Soviet rocket launchers, effectively recycled from old choppers and mounted on pick ups.

A distant heir, for astuteness, of the Stalingrad soldiers who would send dogs with dynamite into the nazi lines, (the rebels have actually been known for sending out reconnaissance dogs with flashlights in the outskirts of Tripoli), this army of its own shared with its precursors the strategy of provisioning: 75% of the ammo, affirmed a rebel, had been looted from the enemy forces. The statement seemed reliable, if we consider the often bare footed state these troops were in: the only Nato-vehicles in sight on this side of the front were local black cars with a large white N painted on the hood, not a joke, as one might think, but a measure of protection from possible friendly fire from above, they said.

Misrata was besieged on two principal front lines: on the west side, Dafnyia, 40 km from Mysratah, was facing Zlitan. On the eastern outskirts, Karareem confronted Tawergha, where the population of color was traditionally loyalist: also a civil war of black vs white, the conflict uprooted people from east to west and vice versa, out of allegiances or coercion.

Gozeelteek, a ghostly hotel with a bombed-out wing, had been deserted even by journalists: in order to encourage them, the media center and radio Misrata were courteously putting up the brave ones left, breakfast included. There we had, at 5 am in mid june, our first unconscious grad missile experience, likening a thunderclap from a 35 pounds dumbbells being dropped a couple of floors up.

At Gozeelteek, as an unconventional security measure, you couldn’t even lock yourself up in your room, because there was no key. Next door right, Portia Walker of the Washington Post and Ruth Sherlock of The Telegraph had blocked their door with furniture for good, they used the balcony we shared to get in, the first time with a vigorous jump, which scared the daylight out of this writer’s soul, screaming her guts out and ready to surrender her throat to the knife wielding cutter.

Next door left, the beautiful face of Chris Stephen of The Guardian, never to be seen again on the screen, protectively blurred in his You tube interviews, probably from the name he has to carry.

Kahlil, a guest of the hotel originally from Zlitan, had come back from London “to help his brothers” by fighting his former city from the Dafnyia front. Those who had been deported by Gadhafi from Misrata to Zlitan, during the Misrata Spring, were forced to bomb their city of origin. Kahlil recounted, at breakfast, that when a grad missile was launched into town, massacres of large proportions were avoided thanks to them, the deported rebels, who didn’t screw the self-destructor on the grad at the moment of launching. The devices, which normally would provoke the grad explosion and were rigorously kept apart from the rocket for security, were surreptitiously hidden in the sand by the “traitors”.

On the other hand, the “desaparecidos” from Misrata were men of the opposition taken away from their family in the same period, but not for fighting. We met them when talking to the people: in one day only, two fathers claimed back their sons, and a son claimed back his father: they all wanted to have the kidnappings reported on Al Jazeera.

On the 16th of June, the pick-up driver had taken us to the path beyond the last container, most probably the Dafnyia dirt beltway, protected by berms of shoveled up earth, along which we could ride looking for best shot, but beyond which we dared not go. Our fixer was the commander of the katiba Al Sumud, “The Non Surrenders”, same as Saddam Hussein’s resilient, UN banned missiles. He explained that Katibas often included men sharing the same occupation in civilian life.

Here the shababs sipped and shared their tea with us, in a moment of pause, where the language barrier was overcome by all of us, by reiterating the mantra “Gadhafi out” ad nauseam, accompanied by the hand gesture of slitting one’s own throat. We stayed until 6 pm, when the mortar bombs started to fall. The commander turned his face up and lifted his arms up and out, as if contemplating a benevolent rain, identifying them as “hown, hown!!” (Arabic for mortar). These bombs were usually responsible for the typical black halo around the breaches in the walls of Tripoli street, Misrata’s main avenue whose videos got blanket media coverage.

In order to see the howns, since we had to live with them, we went where Gadhafi forces left them: on Tripoli street there was a weapon’s fair displaying exploded mortar bombs, the tail fitted with a full around crown, and not much else, the tip and body mostly blasted out. The grad, a 3 meter long missile with a range of up to 40 km, was the main showpiece of that blasted arsenal, made of artifacts of the springtime slaughtering.

27 th June. Dafniya was most of the time off limits. A colleague at the hotel suggested to jump in an ambulance. We requested a lift to the Al Hikma hospital, situated at the beginning of the road to Dafniya, which served quite well as an indicator of the situation at the front: empty emergency area, Dafnyia “myamya”. The strategy was almost perfect, the driver not allowing us into Dafniya, and dropping us off at the field hospital, at approximately 4 km from the front line. “This is where the wounded soldiers are first taken”, said a doctor, so they won’t die before they are taken back to Misrata. A man was dousing the ambulance floor with a water hose, turning the saturated red to clear.

At the gate of the driveway to the hospital, at approximately 5 pm, multiple grads hit the ground, like craters erupting in near unison. Too close for comfort. One turns around, and around, and there are no craters, and one is afraid to step into the next crater, or to stay and become the next crater. The drivers coming from Dafnyia, who usually slowed down to say hello with the V sign for victory, were zooming by like bullets flying into the city, and so did a car coming from the hospital, leaving us standing there.

Back at the hospital, the staff confirmed that three grads had actually hit the tomato field, which provided the main ingredient for the daily-baked pizza for the army, then ordered positively not to disclose to the media where they hit.

The 2nd of July. An empty tent at the Al Hikma hospital, Dafniya myamya, we took off again. The freedom fighter first took us for a tour along the beach to see the Chinese development binge: the construction of the huge condo buildings, about 5 km long, was on hold for the duration of the revolution, he explained, and scheduled to resume, hopefully, quite soon. Then he stopped on the way to Dafniya to practice his machine gun.

Standing up in the back of the pick up, he fired away from behind a flat metal shield all the way up to his neck, making the kalashnikovs on the back seat next to us rattle and shake and nearly drop and hit the car floor. At Dafnyia, a mujah, taking advantage of the endless stalemate, was sleeping right on top of the dunes in the last container (helas the last for the last 6 weeks), holding on to his AK 47 in his sleep. Another was preparing to launch a rpg, which in Libya is usually referred to as rgb, like the acronym of primary colors, red, blue and green.

Dozens of pick-ups, coming from the city were carrying rajima rockets launchers, lodging 12 missiles of 8 km range, to the southern flank of the front. The poor relative of the grad, which can reach as far 40 km, but of the same 122 mm caliber, the rajima is also shorter, and represented the most ubiquitous weapon in the rebels’ sui generis ammunitions’ insalata.

The 8 of july, return to safe haven Benghazi. On Al Jazera, a reporter in Dafnyia showed what just yesterday had been the furthest position for 6 weeks:

the abandoned container where the shabab slept, the dunes on the container covered by a barrage of bullets. “Not to worry” reassured the reporter, they are doubling down exactly 6 km further: after 6 weeks of impasse, a new container had been placed just 160 km west from the snake’s head in Tripoli.

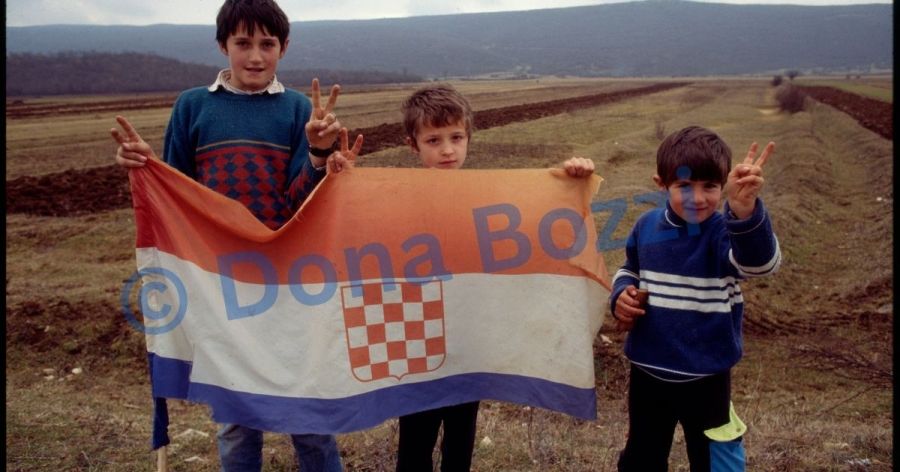

On the road to Ajdabia, at the last check point before the city, some kids in uniform, by then part of a regular army of the revolution, posed proud for the camera with a brand new battery of their own brand new “hown”, made -they said- in South Korea, and a line up of their own grads, just out of the box from Russia, some still in the package marked “explosive”, guarded by a sleepy soldier lying on a mattress.

The 23 of August: it’s hard to sit pretty across the sea when Tripoli is being taken; Rome, Cairo, Xandria, back to the waste swathe before Libya: at the border, the chief inspector was a member of the Abdullah Al Zanussi family, a prominent Tobruk family who was part of the Tobruk PTC (Provincial Transitional Council). He recognized us from our previous entry visa and we congratulated him for the job well done. Next day, three young men stopped their Toyota pick up rolling down the window: “Benghazi?” We jumped in, after 15 km, they made a right turn towards the fourth Italian shore. At the beach, the man next to the driver pulled out a knife and handcuffs, so we threw mac books, cameras, Euros , and shoes at them, in exchange for an open car door, a deal they seemed quite happy with. A handful of Euros, which were meant to fantastically multiply by two, once exchanged into dinars at the black market behind the hotel Dojal!

The gang escaped with their loot, taking along with, them, inshallah, the wacko with the handcuffs calling out “jeans!” from the front seat. The people of Tobruk (who oddly enough, mentioned more often that “Rommel passed by here” rather than Montgomery) picked us up barefooted, and the Abdullah al Zanussi family put us up at the 5 stars family’s hotel, Al-Masira, apparently “march” in arabic, named, it was rumored, by Mussolini.

In the hall, it was Al Jazeera all the time, and that meant Libya all the time. The leader of the rebels in Tripoli, Abdel-Hakim Belhaj, the Americans were concerned- was supposed to have ties with Al Qaida, and had exhorted the rebels not to hand in their weapons. Also,the emir of Qatar, who financed the revolution, is some kind of a wahabist, leader of an oppressive regime.

Jamel, a Dafniya rebel, however, did wave his index finger at us, declaring: “No bin Laden!” He admitted that his all-time hero was Fracesco Totti, the king of Italian soccer.

During out on the town time we were escorted at all time by Farraj, – his real name – a cop, just in case the wackos would show up again. In downtown Tobruck there is a tiny tiny church, all boarded up. In spite of all the sour feelings, Tobruck residents didn’t take it down, because, he said, the Libyans didn’t mind the Italians after all.

LIBYA IS FREE: Saif al-Islam Gaddafi ‘pretended to be a camel herder’ when captured Captor says dictator’s… http://t.co/9qFUaOxB

— LIBYAN REVOLUTION (@LIBYANREVOLT) November 20, 2011

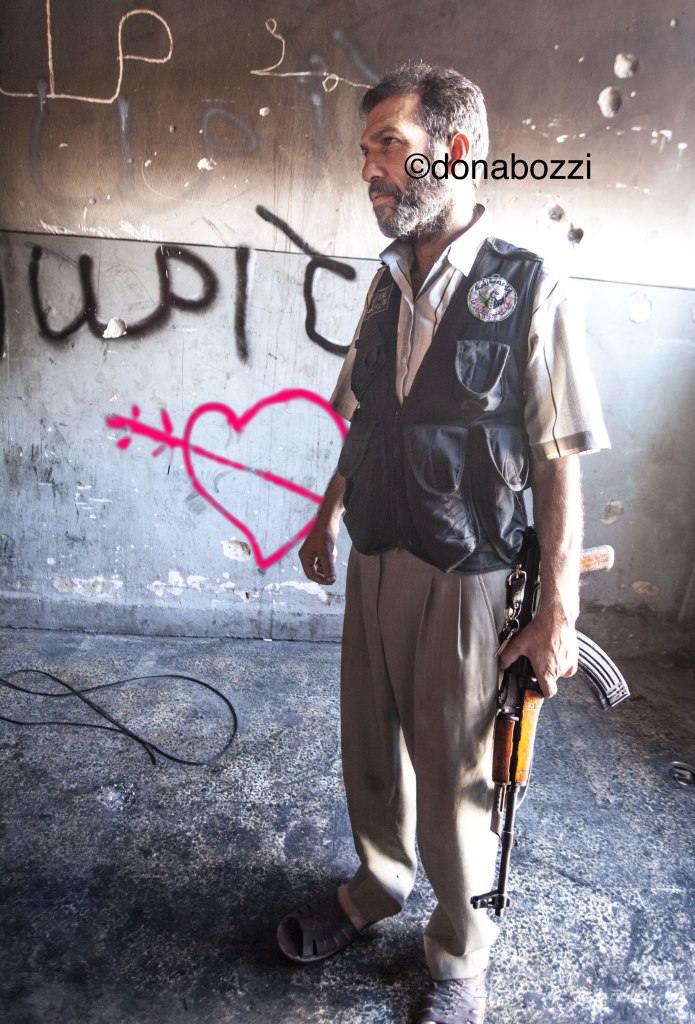

The old district of Bab Al Hadid, the Iron gate, surrounds the ancient Citadel and its hill. In the neighborhood, every battalion has its own front line, except for larger brigades who fight on more then one.

A woman with more then one stray wisps of hair poking out from under her veil, and ash blond at that, walking down the cobbled streets of Bab Al Adid, waving to a stranger, didn’t fail to impress commander Sheik Kattan, who pulled over his pick up to engage in conversation. He is in charge of the artillery of the Ahrar Syria brigade ( the Free people of Syria) one of the largest in the city, about 5000 men, and he is willing to show us the rebels’ experiments at casting their own barrels. On the way, he lifted the cover of an intriguing tunnel, looking from the asphalt like the regular cover of a city conduit, but used instead by the rebels to penetrate into enemy’s neighborhoods.

Where exactly the tunnel would end up, he wouldn’t say.

At the command center, he produced for us the performance of fire by lighting what he called magic cotton, which is regular medical cotton which underwent a chemical treatment with potassium nitrate, ammonium nitrate and acid. “What kind of acid?” , I asked him. “Acid, just acid.” As a result, the cotton becomes highly inflammable and it’s used, as he demonstrated, to fill up plastic cartridges to be inserted in equally hand crafted guns.

“Where did you import the process from? Afghanistan?” “No, we were discouraged because nobody wanted to help us, so we searched the internet”. Commander Kattan then proceeded to show us a home made rpg shell which costed him 5 dollars to make, as opposed to the ones found on the dried up Lebanese market for 800,000 dollars.

The 140 mm artillery and the shell which he dropped in it were also products of their own experiments in metallurgy , and so were the 3 kg missile and its launcher.

The jewel of the ammo was an ingeniously thought out dynamite launcher gun they nicknamed bombaction: the empty casing of a doshka bullet is filled with dynamite powder, then dropped into the tip of the gun. A cartridge filled with magic cotton is then placed inside the gun, which gets ignited at the triggering, thus propelling the dynamite launch.

Asked if the defeat of Qussair represented the loss of a supply route and troops to the Idlib province, Mr Kattan replied that the road was still in use, and they withdrew temporarily just to save civilians lives. “In Aleppo, we pushed the shabiha back to their neighborhoods and the citadel is ninety per cent taken”. Then we asked Mr Kattan to take us to the real thing. His men took us to unsuspected front lines, on the top floors of ancient burned buildings concealed by regular looking facades, up on the familiar tour of the rubble:

In Aleppo’s Bab Al-Hadid neighborhood, or Iron Gate, between buildings held by the Free Syrian Army and the regime, shouts, then fire, were exchanged. The men of the Ahrar Syria Brigade (Free Syria) were the stokers; with temerity, they yelled “Shabiha! Shabiha!”, through rubbly breaches, standing around a building corner, atop ramshackle roofs, into surrounding regime held blocks. Annoyed that the mice hadn’t come out of their holes yet, they continued to shout insults: preferring to wait for darker hours, the Shabiha didn’t accept the invitation. So we would wait too, standing with our back against a putrid wall, feeling unsheltered as we looked out the wall-less side of the kitchen, now become an unglazed panorama over the remains of the Iron Gate.

Our friends, pointing at the snipers’ shots on the wall behind our shoulders, advised us to move over to a surprisingly safer spot: right in the open. We preferred to move. While moving building to building or even from a kitchen to a bedroom, missing or broken wall occasionally exposed us to the Shabiha’s view. We were thus advised to run. And so we did along the sniper alleys of the Iron Gate, back to the future from the siege of a city in a previous European war, two borders up, promised to be the last mass grave, the last stolen country.

Back to Bustan Al Qasr. Toni, the head of the AMC, proceeded to recount the real story, or history, of ISIS: “More and more Iraqi fighters were coming in, joining Al Nusra, sent in by Abu Baker Al Baghdadi to cause trouble, starting to interfere with people’s lives and kidnapping journalists. Baghdadi himself announced the merging of the State of Iraq with Syrian Al Nusra (the Sham); that made the Iraqi elements feel entitled to steal our weapons and money. Al Nusra’s high profile men lost control, and kept their head low, waiting for orders from their chief Al Golani, who declared he did not want to merge with Abu Baker and ISIS, however he did pledge allegiance to Al Zawahiri as a leader and a person, but not to Al Qaeda as the group. Al Zawahiri then disbanded the merger (we forgot to ask if he did encouraged it in the first place) and ordered Bahgdadi back to Iraq, and Golani to stay put, thus encouraging fighters to defect back from ISIS to Al Nusra. Baghdadi violated Zawahiri’s order and stayed in Syria, thus radicating terrorism in our Country.

Back to our rooms, we celebrated a long awaited trickle of water, tapping into the resource at a prodigious rate to fill a dozen bottles before it came to an end, and taking showers as if there was no tomorrow. Then by the light of the beam of the open mac book we went downstairs, mischievous kids popping out of dark corners, one of them pulling a serious kitchen knife out of the dark, all he had found to play with.

In the heyday of the Aleppo revolution, supper was extravagant even for spoiled western European standards: about twenty kids would take a break from laptopping the revolution, stand around a chairless table, stick their bumpy flat bread into tahini butter, made from freshly ground sesame, picking up roasted chicken with the folded circles, complaining that the cook wasn’t up to snuff, and wondering if I had a younger sister.

The first jihado nicknames however would start to bubble up on FB, and bad looking dudes in black with guns at the AMC gate, would gesture unfriendly to us “picture verboten”: the media center was soon to become an oxymoron for journalists, along with the fact that the regime, probably according to a “pattern of life behavior” had started to pick on us with what sounded like grad-thuds on our roof around 5 o’clock am.

But times were changing, as experienced by this writer, caught one morning inadvertently veilless at breakfast: veilless at breakfast is anathema enough in any Muslim country, even in tolerant not yet beard peaked Aleppo: Sami, our fixer, revealed that rumors had been circulating in the building about an undetermined number of wisps permanently poking out from under my hijab. The Administrator, look from jihadi central casting, disclosed a long buttoned up feeling, unbuttoned: he drew endless loops with his index finger around his face, meaning “the veil”, then he flashed his swinging open palms up at me, clearly conveying the international “that’s it” injunction. We were escorted to the available ramshackle car, Sami in the front seat, as an interpreter if needed. We drove up north 20 miles from Azaz, where we were courteously dumped at a bus stop, not in an unfriendly manner, bus fare to Kilis courtesy of the house. Sami ordered to write as soon as we had crossed the border, and I obliged to his 10 years older then real birthday Fb profile; he confirmed to my next fixer, that he “protected me as a woman in a warzone” and reiterated not to worry, it’s not uncommon that Syrian may be wary of journalists, even those who not so covertly root for the revolution.

russian backed pro regime forces arrive in #Raqqa Russia who’s allied w/US who’s not so allied with regime, or not?https://t.co/9ikowWSsv4

— dona bozzi (@donabozziblog) May 21, 2017

I would like to thank all the humans whose stood for the humanity with our case, i will never forget you if we passed to the other life

— Monther Etaky (@montheretaky) December 12, 2016

Our contact in a Turkish city which cannot be named for his protection is Ammar Cheikh Ammar, a German/ Syrian army deserter become media darling, interviewed by the New York Times Soldier Says Syrian Atrocities Forced Him to Defect and by German television DW, presented by them as Omar Sheikh Ammar, and showing in the comments as, what else is new, “a Jew on the whorish media’s payroll”. He’s our liaison with Aya in Gaziantep, where the fashionable spaghetti straps of Istanbul and Antakya give way to non-sexual dark veils. She is with Nsaeem Syria FM, (a pro Revolution radio station), meaning “Gentle wind” and claims to be a part time fixer, having helped into Syria la crème de la crème of international journalism. In her room, a blood type silver tag with the words Al-Tawhid, and Free Syrian Army, oddly engraved together, lay on her bedside table. In NPR Fresh Air, May 1st, 2013, https://www.npr.org/player/embed/179855633/180037134, New York Times correspondent J.C. Chivers described indeed the most effective Aleppo brigade as an Al Nusra affiliate. Whether this is the case or not, in Aleppo Al-Tawhid is considered mainstream even by the moderate opposition itself: “The FSA and Al Tawid are actually the same thing, in that Al-Tawhid operates under the umbrella od the FSA”, Anas Alhaj, with the Council of the Governatorate of Aleppo, will proudly explain later to us in Aleppo. Aya never procured us a fixer, although she went on a shopping spree with the money we gave her so she could find us one.

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jsI can tweet now but I might not do it forever. please save my daughter’s life and others. this is a call from a father.

— @Mr.Alhamdo (@Mr_Alhamdo) December 12, 2016

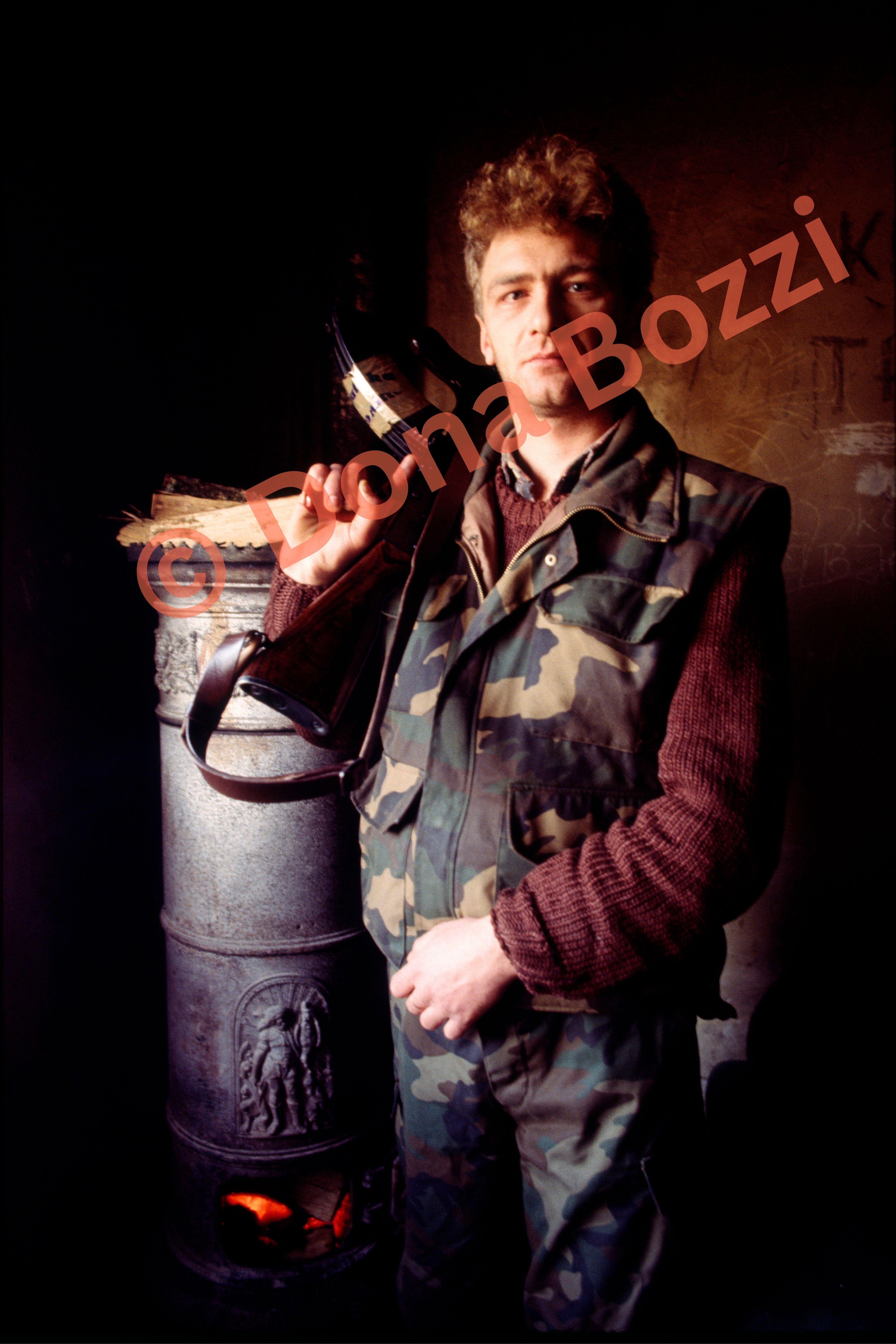

One of the front lines of Aleppo is at Kafr Hamrah, between two buildings, not even one kilometer from one another, in the northwestern countryside of the rebel held east side.

One of these buildings is under the Free Syrian Army, the opposite is regime held. The katiba (battalion) defending the FSA’s building is named “The revolutionaries of Manbij”, one of the most respected and effective in Aleppo. Within the FSA, this katiba operates under the banner of Al-Tawhid. Every katiba has a Mullah, who’s also a combatant, teaching the fighters not to steal from, and not to hurt the people in captured territories. This katiba also has a doctor, a teacher of primary school, and a mechanic. The headquarters are in a previously magnificent Scarface-style of villa, complete with dried out swimming pool, that the revolutionaries have taken over from whom was wealthy enough to escape the remains of murder. We met the fighters over a breakfast of dried out dates, stale bread, and the only available safe drink, ubiquitous mini bottles of saccharine orange juice which made us thirsty. In not yet beard peaked Aleppo, some boys had grown enough hair to look, at worst, rogue renegades on the margin: the home grown Aleppo mujahid were not going to carry out jihad, just practicing the business of amateur insurgence.

Anas Alhaj, our fixer, with the Relief Committee of the Council of the Aleppo Governorate, said it’s a good thing that Hezbollah, the party of Satan, and Iran , came to fight on Bashar’s side and unveiled their true colors to the Sunni of Syria, who now knew who the militia really stood with. In fact, before the revolution, the Sunni used to root for Hezbollah, because they also were Israel’s enemy. ” Back then, even Iran was not an enemy”. In his fervor, Anas disregarded that Hezbollah did remain Israel’s enemy, even if, in the topsy turvy politics of the Middle East, having a common enemy doesn’t necessarily make an alliance.

At the helm of the oddly luxurious command post, Commander Abu Farouk, one of the most respected leaders of the FSA in Aleppo, candidly declared a nom de guerre: who would give his real name to a journalist in Kafr Hamrah, anyway?

Before taking us to the front line, he coached us word-by-word to recite the Shahada, the Islamic creed declaring belief in the oneness of God and the acceptance of Muhammad as God’s prophet, which would make us, just in case, die as Muslim: “Ashhado ana La Eelaha eLa Alah, wa ana Mohamad rasool Allah”, “There is no God like Allah, Mohammed is the prophet of Allah”.

The “front line” is about a five-kilometer drive from the villa. We climbed to the top of the building. A rebel showed us the blood, on the stairs, of the last body that was dragged out, “about a week ago”, they said. On the top, two awfully young boys kept on guard, seated by the open wall, their back stuck to the back of their chairs, staring at a broken mirror reflecting the enemy’s position.We asked Abu if he could tell, from the shouts from the other building, who was on the other side. ” Mostly Farsi, from the Basij, (the militia established in 1979 by Ayatollah Kohmeini) and the pasdaran (the Iranian Revolutionary Guard)”, he replied. “Lebanese, Iraqi and Yemeni Shia accents. Turkish spoken by Turkish Alawites, and some Russian, probably spoken by Kazakistani, whose country is eighty per cent shia”.

“When we shout Allah uakbar, we hear scared voices from the other side invoking: “Oh Hussien, oh Fatima”. (Hussien was the son of Ali Bin Abu Talep, the cousin and son- in- law of the prophet Mohammah. Fatima was the daughter of Mohammad)”. They can hear the Rafidah, (the infidel shia), by ingeniously tweaking the wavelengths of their sort of old fashioned walkie-talkies.

“These gadgets are part of the “non lethal aid” recently supplied by the US”, together he added ironically with a grin, a subtle smile, The “Friends of Free Syria” did not open the gates yet to flood Free Syria with the MIM – 104 Patriot anticraft! Commander Abu Faruk was kind enough to take us back after a few camera shots, besides those aiming at us from the opposite building. However, before we left, we had one last question for him: – Wasn’t it wicked of Al Zawahri (head of Al Qaeda) to urge the merging of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Sham with the Syrian affiliate of Al Qaeda, Al Nusra? Trying to deter arm shipments to the moderates by further contaminating the opposition resulted in augmented hesitation by the west to support the revolution all together. In fact, Al-Zawahiri himself had to retract the invitation, in the aftermath of the atrocities committed by the network of death. Commander Abu Faruk, a military man and not a think tank strategist, didn’t have an opinion on that: he was a Muslim revolutionary from the FSA, and didn’t give a damn about the Islamic State.